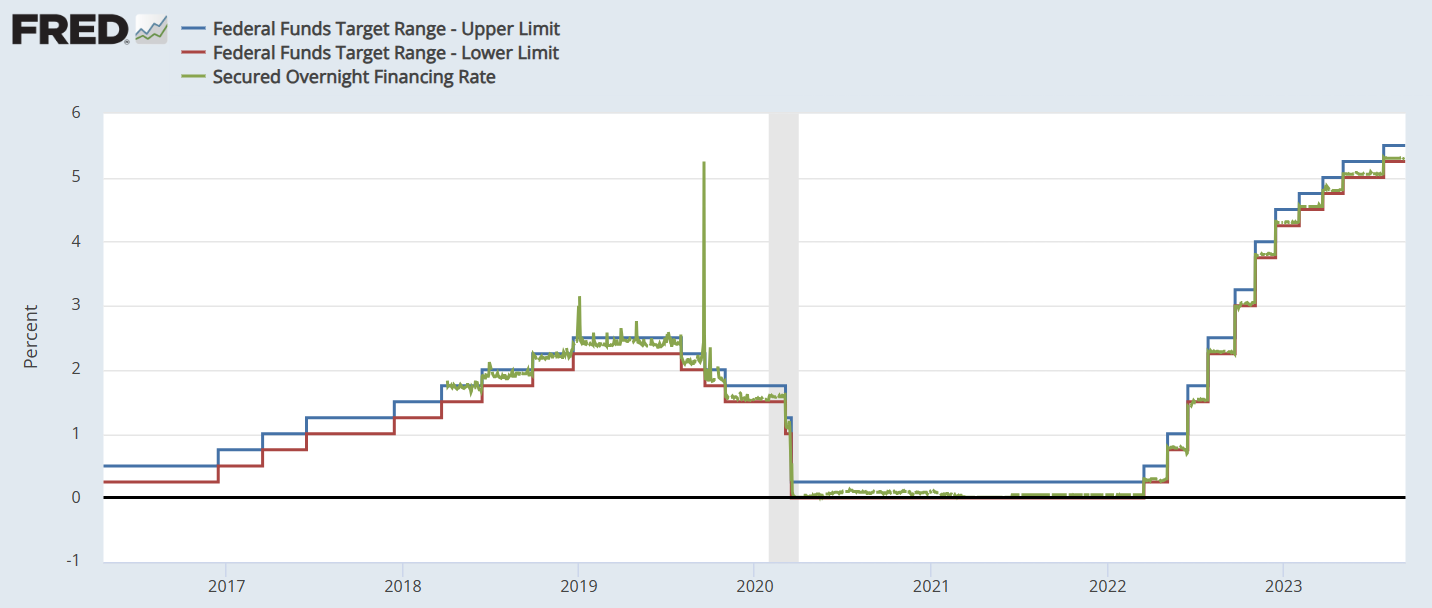

In 2022, the Federal Reserve embarked on a historic journey, raising interest rates at an unprecedented speed and magnitude, a move that surprised many and left economists and observers alike scrambling for explanations. On March 16, 2022, the Fed initiated its most aggressive hiking cycle ever, a stark pivot from the predictions of its own Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) just six months prior. This introduction explores the myriad reasons behind this drastic shift, diving into the narrative that starts with the epic COVID fiscal stimulus and the resultant spike in the money supply, and the subsequent rise in consumer prices and inflation.

It examines the Fed’s initial dismissal of inflation as “transitory,” its eventual realization of the long-term nature of inflation, and the urgent, rigorous rate hikes aimed at restoring its credibility. However, the introduction also delves into the broader implications of such a move, questioning the Fed’s motivations and the political and economic intricacies that drive such significant decisions. This is not just a story of rates and inflation; it’s a complex tale of credibility, political choice, and the delicate balance of monetary policy.

So Why did the Federal Reserve hike interest rates at the fastest, most aggressive pace it ever had in 2022? On March 16, 2022, the Federal Reserve embarked on its most aggressive hiking cycle in history. Six months earlier, nobody on FOMC predicted they would pivot to such hawkishness.

Credibility

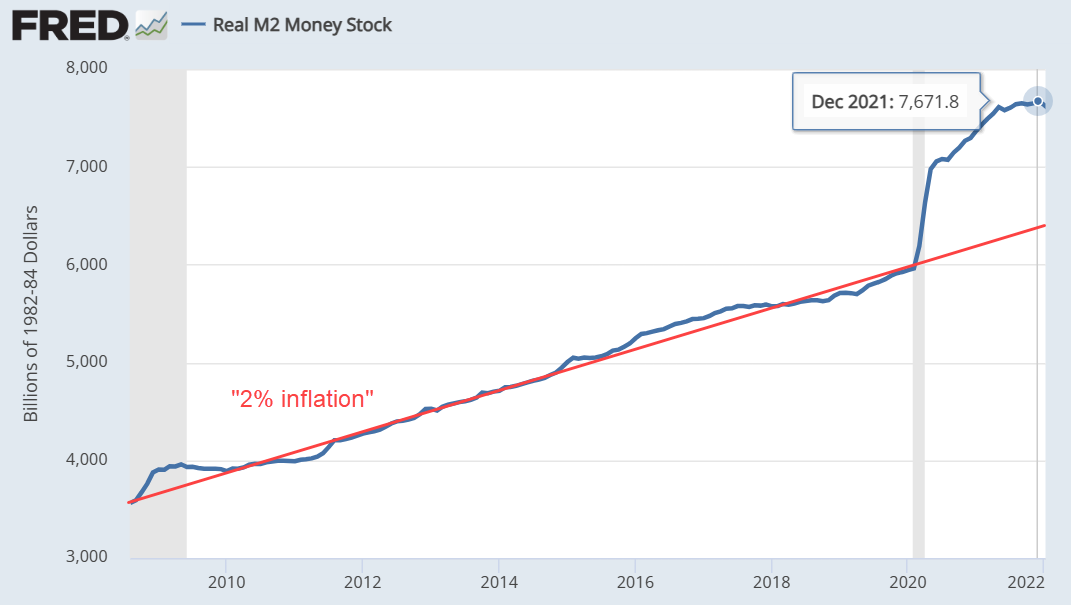

The narrative goes like this: the epic COVID fiscal stimulus and spike in money supply to far above its recent trend line…

Until 2020, money supply (M2) had grown at a fairly steady rate of about 4% per year, with inflation steady at about 2% per year. The red trendline is arbitrary.

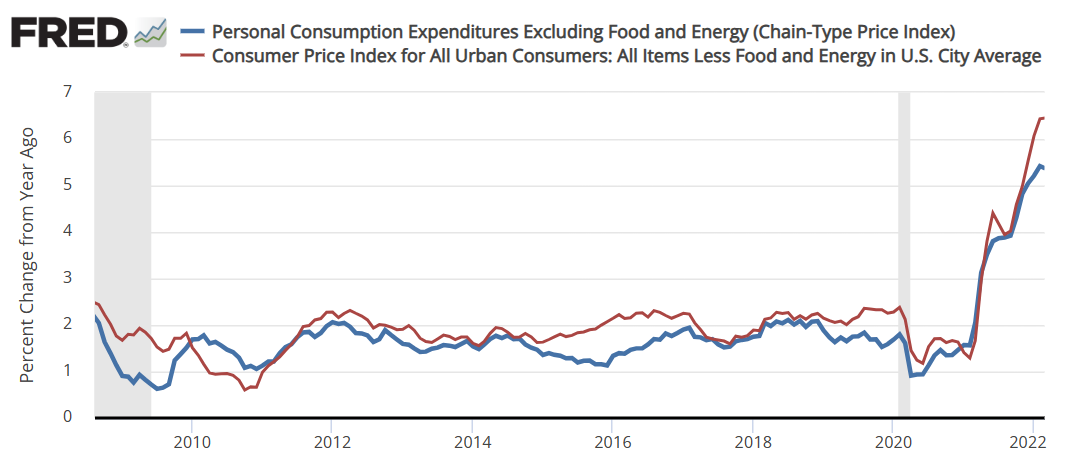

…caused a corresponding spike in consumer prices:

Core inflation (blue) peaked in March 2022. Headline inflation (red), a little later.

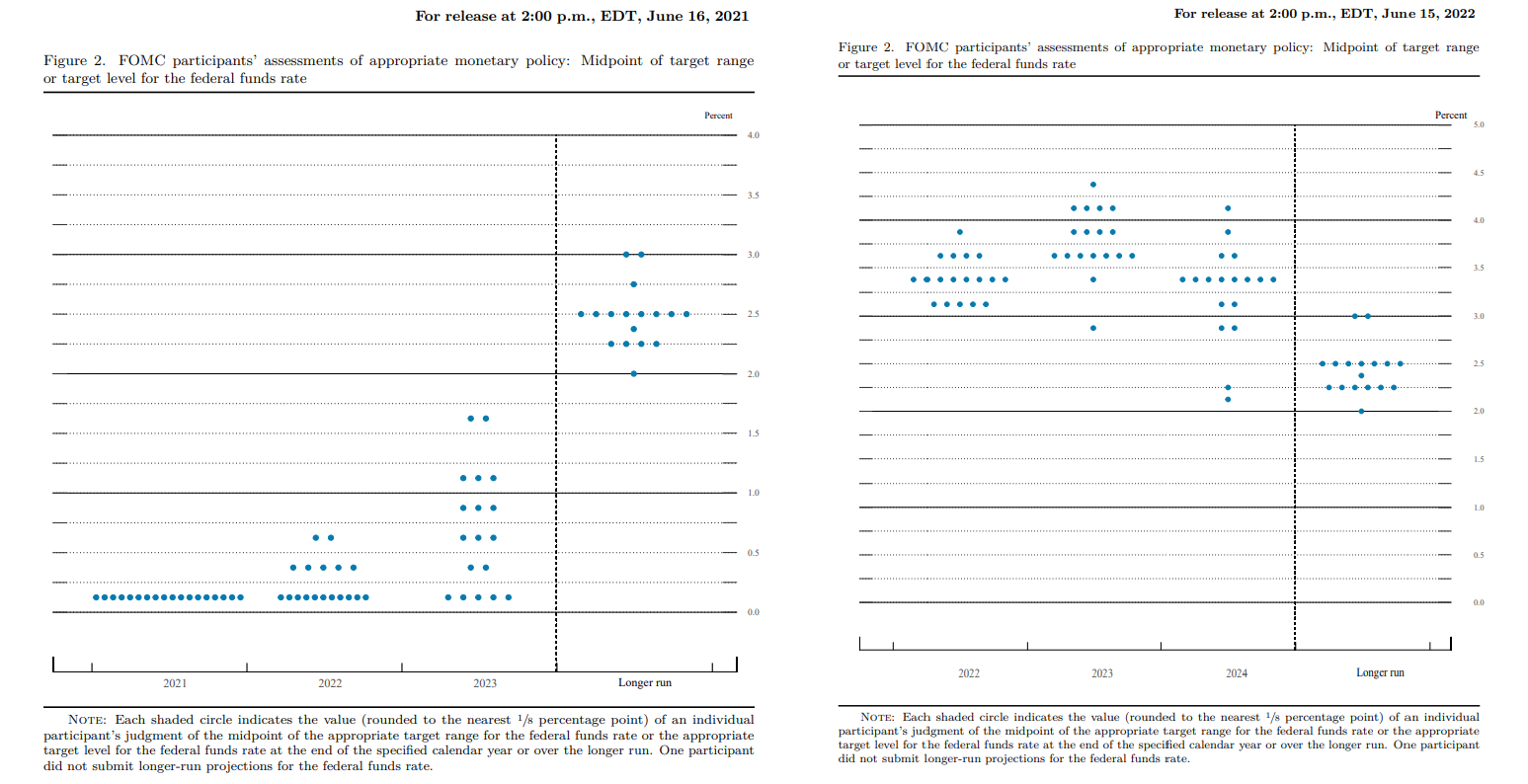

As inflation began to steadily creep higher, monetary officials dismissed it as “transitory supply effects” and, throughout most of 2021, FOMC members maintained that interest rates could be kept at near-zero through 2023.

June 2021 SEP (summary of economic projections) versus June 2022. At some point, Fed officials agreed that ZIRP was unsustainable.

At some point, the Fed realized that inflation was indeed not transitory, and so began the historic rate hiking cycle of 2022-23. They tell us that they had to “catch up” on inflation, with seven consecutive rate hikes, in order to “restore their credibility“.

To Americans, the Fed is only credible absent rampant inflation and unemployment.

But is this the full picture? It was widely known that higher rates would create bank asset-liability mismatches, fiscal crises in emerging markets, and higher debt-servicing costs leading to waves of failures and defaults.

It took only a few hours for the media to acknowledge that higher rates would bring pain.

In other words, it was widely known that suddenly pivoting from ZIRP to 6%, and then steepening the yield curve without rate cuts, would lead to pain and recession.

So whatever the reason, it must’ve been a very important one.

NYT: Powell “pivoted” from transitory to persistent inflation because of new data (and therefore decided that they needed to hike to 6%?).

There’s no doubt that the Fed’s credibility on Wall Street is important, and part of that credibility is in control over price stability. If the Fed were to leave the U.S. economy in an inflationary mess, the market may no longer respond affirmatively to what the Fed says or even does. Turkey, for example, hiked their interest rates from 8.5% to 15% on June 22nd. The market responded by dumping Lira. This is diminished credibility that Powell is keen on never facing the Fed.

Here’s the thing about inflation, as former New York Fed trader Joseph Wang reminds us – ultimately, it is a political choice. It’s easy to create – the government can create new programs to give away lots of money. And easy to cut back – the government can raise taxes.

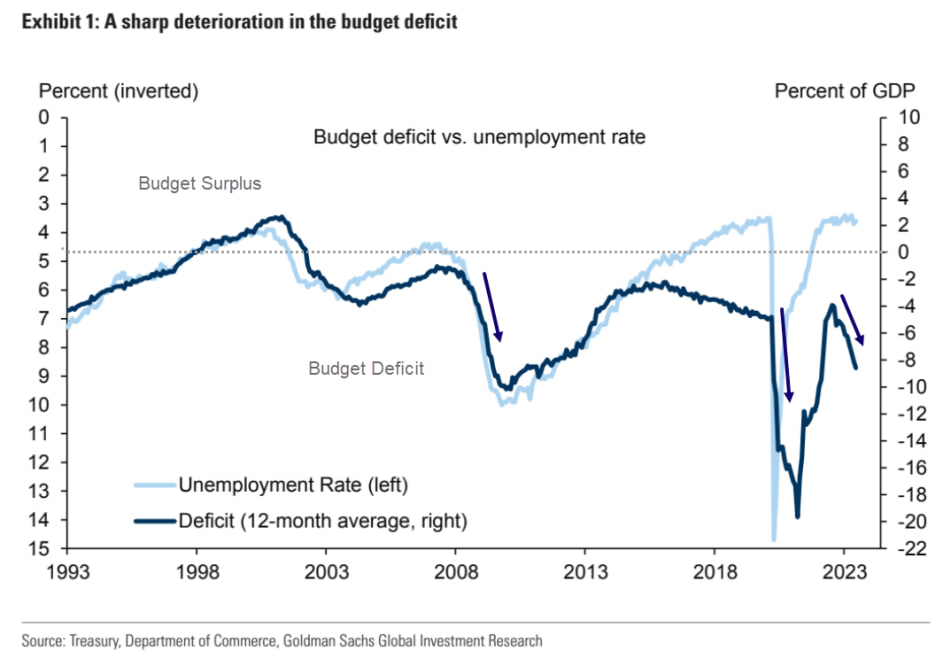

That being said, if Washington D.C. were serious about disinflation, they would not be running 10% deficits at less than 3% unemployment:

Deficit spending is stimulatory and re-inflationary, hence why large deficits are run in response to recession and unemployment: to literally re-inflate the economy OUT of a slump.

But here we are…

For the record, we do think they are very serious. But only insofar as it pertains to the high rates. It’s a ‘chicken or the egg’ question: what begets the other – high inflation or high rates? The Fed, and every public official under the Sun, will tell you that of course high inflation necessitated the rate hikes. This is what Powell will tell Liz Warren each time he testifies in front of the Senate Banking Committee.

So long as inflation is above target, the Fed feels completely justified in keeping rates elevated.

But we believe it to be the opposite: higher inflation justified the high rates but did not necessitate high rates. What then could have possibly motivated the Fed to hike to 6% (and possibly even beyond) in two years?

Repo.

The Fed was forced into a hiking cycle to prevent repo rates from spiking deeply negative and below their administered floor as the world transitioned onto the SOFR secured lending standard.

To adequately understand the mechanics of how this is possible and why this would be the Fed’s nightmare, we need to overview some definitions, revisit some recent history, and describe a couple of scenarios.

It’s a Repo World

Short-term and overnight financing is the bedrock of the U.S. financial system.

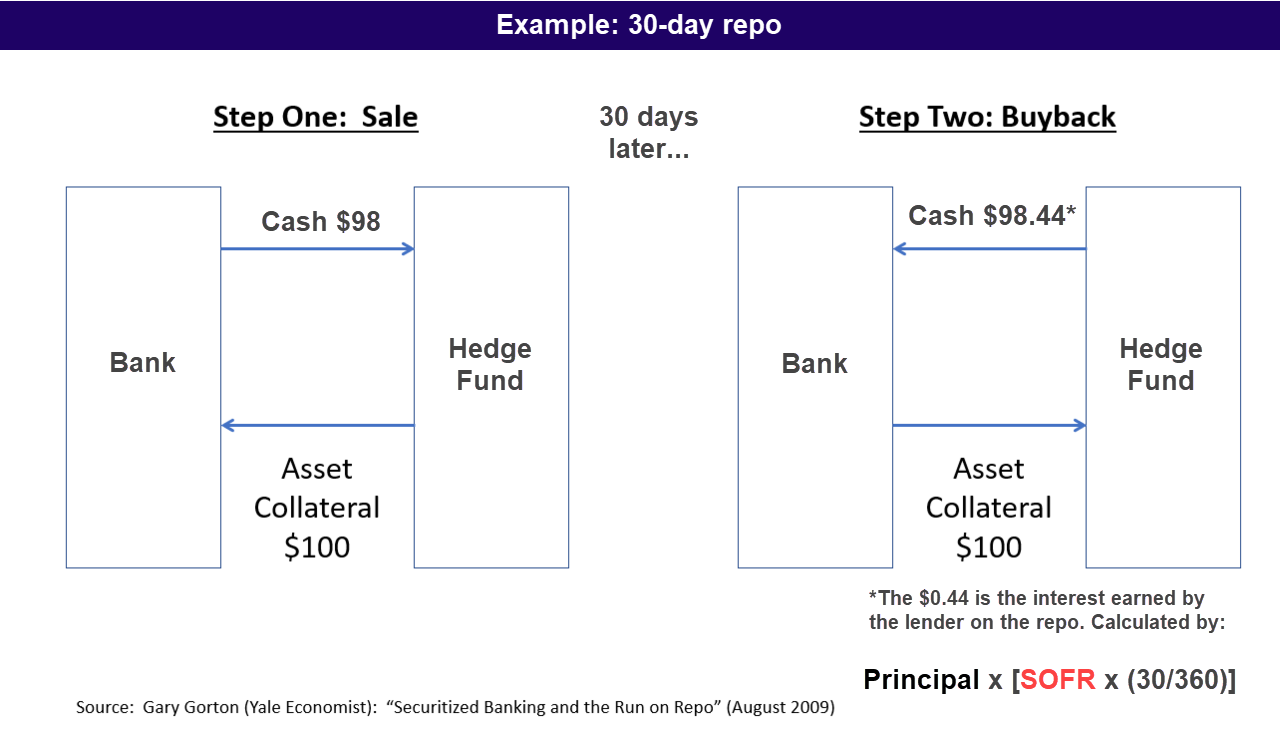

Repos (and reverse repos) are overnight loans. Source: NBER

A repurchase agreement (repo) is a loan secured by collateral. If you are a fund in need of a $100 loan, you can borrow it in repo by pledging $102 worth of Treasury securities (the 2% difference is the ‘haircut’, another layer of protection for the lender) & agreeing to repurchase (repo) that collateral for $100 plus interest. This example is visualized in the image above. The Treasuries serve as collateral – in the event that you default and fail to repurchase it – creating a secured lending standard.

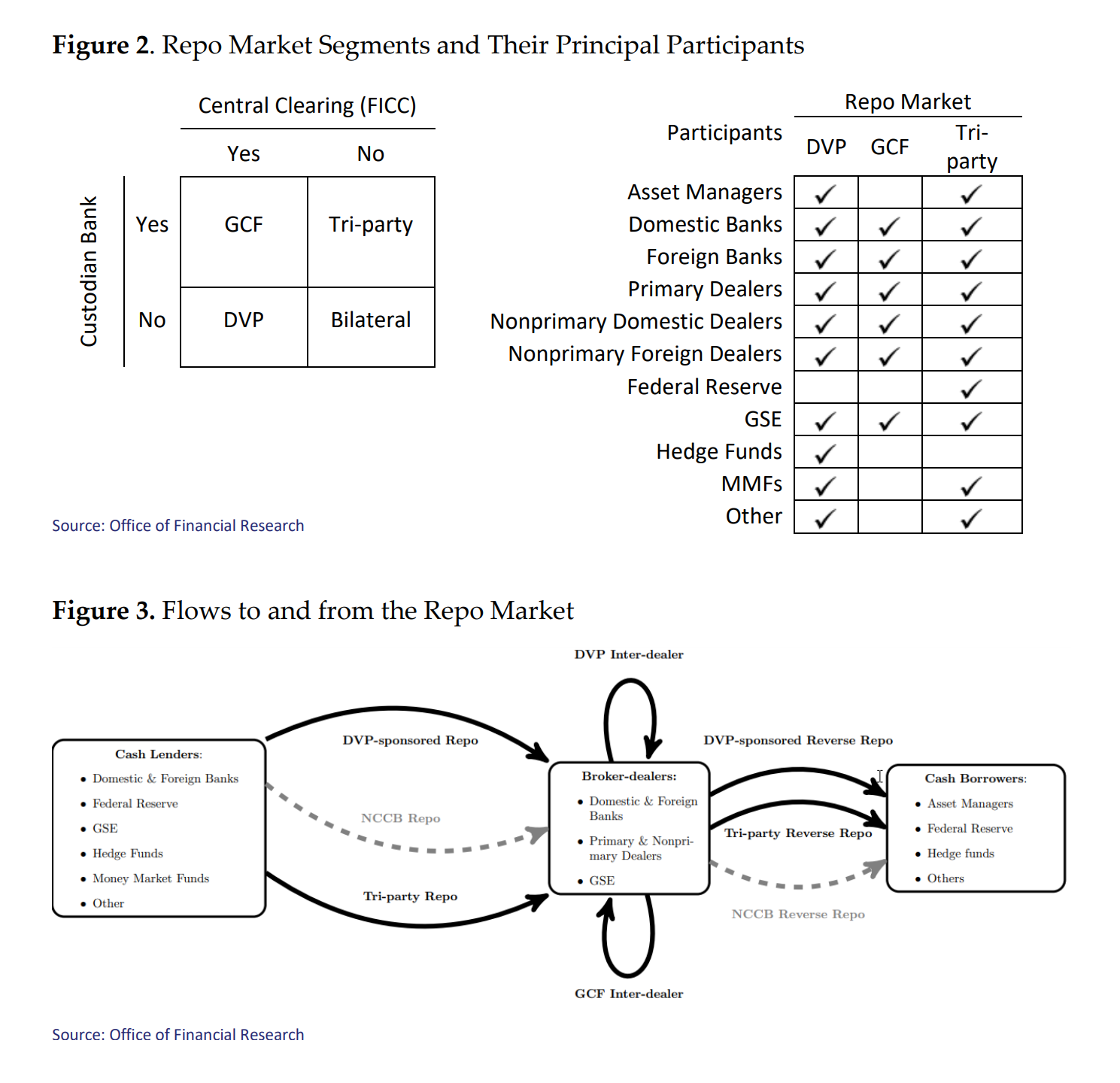

Repo participants can generally be thought of as cash lenders, borrowers, and dealers.

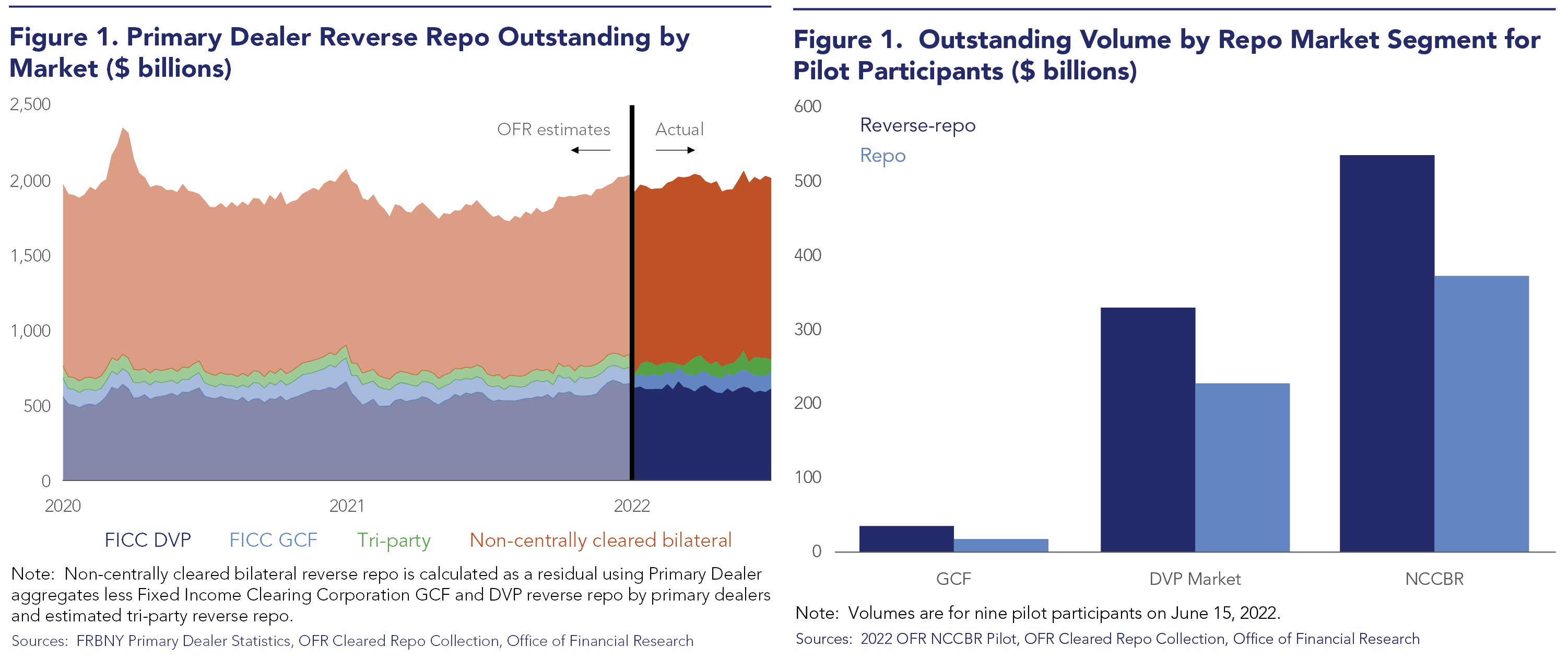

Overview of each repo venue, the participants, and their interaction. Source: OFR “Anatomy of the Repo Rate Spikes in September 2019”

In addition to whether or not the repo is centrally cleared or on the BNYM’s tri-party platform (Figure 2 above), there are some qualitative differences between each of the four venues: size, collateral type, participants, etc.

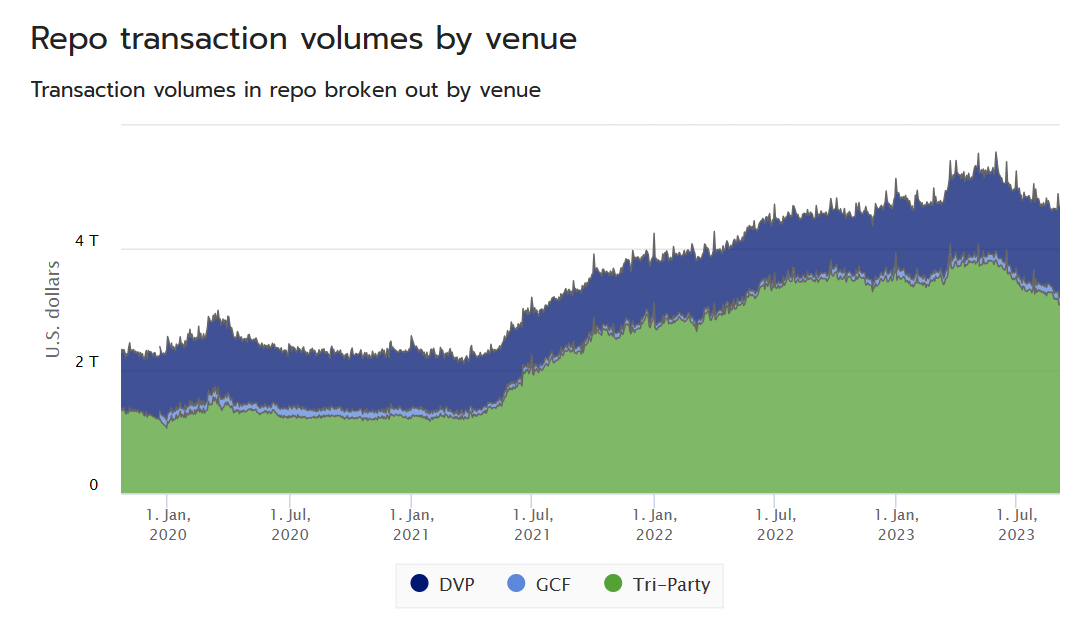

By reported size, Tri-Party – the platform of the Fed’s RRP – is the biggest venue:

The three repo venues with volumes collected by OFR. The Fed’s reverse repo facility is on the tri-party platform, hence why it is so big and why it took off in mid 2021.

But Tri-Party is not the biggest repo venue overall, because non-centrally cleared bilateral repo (NCCBR; uncleared bilateral repo) does not report its volume (at least in the same way that Tri-Party and other venues do. Though this is changing.)

NCCBR (non-centrally cleared bilateral repo) data is not reported like volume in other venues.

In some uncleared bilateral repo venues, you can pledge collateral carrying credit risk, like corporate bonds or even equities. Equity repo would require a much interest rate and a substantial haircut (to protect lender against price moves). This is a relatively small and illiquid segment of repo. Nonetheless, low-quality “junk” collateral is indeed a feature, and perhaps a systemic risk, of NCCBR.

But the point is not to dive into repo – the point is to establish some definitions such that we can better explain what happened, what almost happened, and what will happen.

Repo-Policy: A Ceiling and a Floor

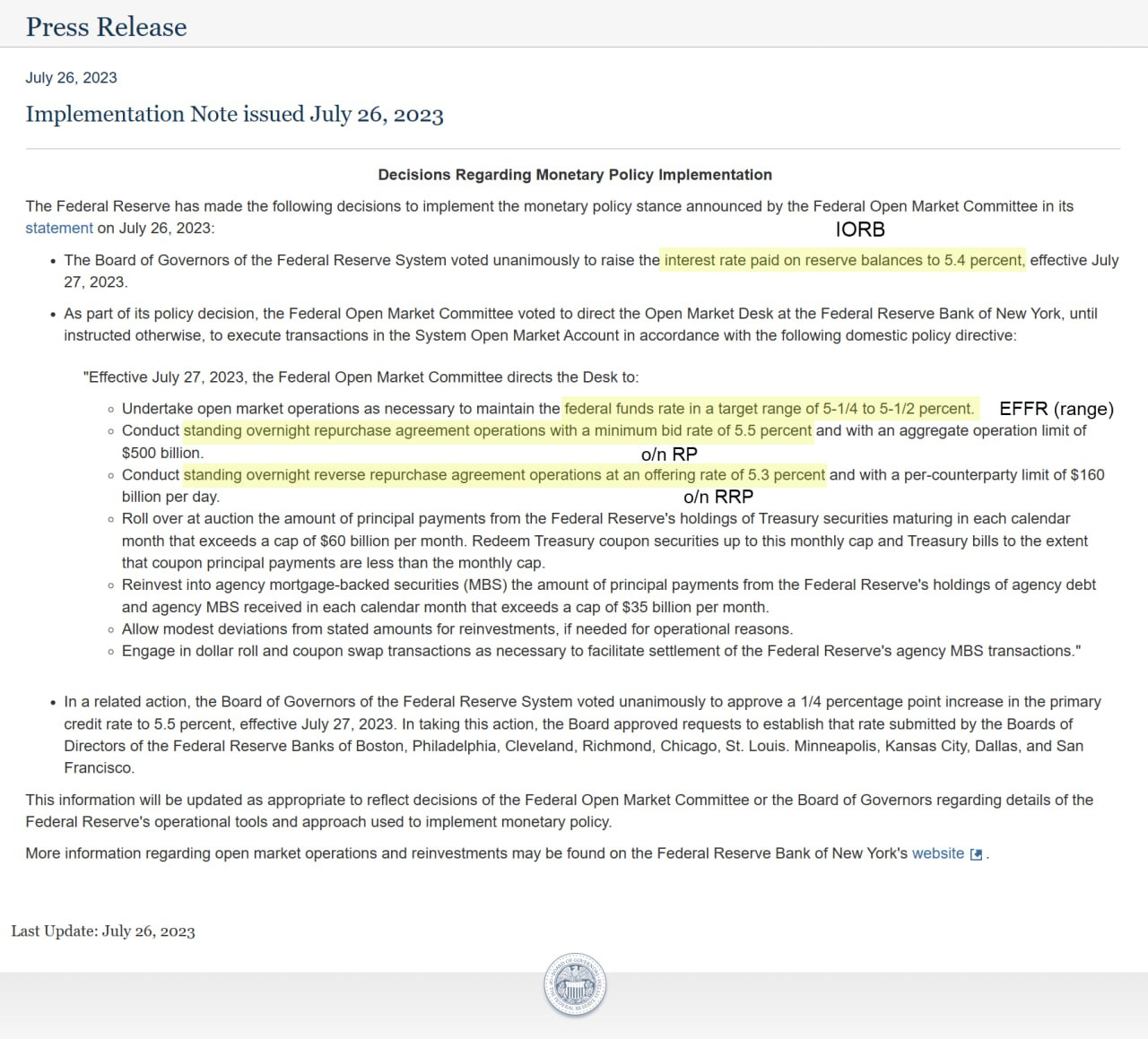

July 26 FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) meeting. FOMC is a rotating collection of Fed Presidents.

Looking at the latest FOMC statement (from the July 26 meeting), we can see that the Fed can really set two different rates, even if they are in a range:

1) the Fed Funds rate target range. This is the range within which the EFFR (effective Fed Funds rate) trades, which is the rate on unsecured interbank lending.

2) the interest rate paid on bank reserve balances (IORB) held at the Fed. Banks can place (“park”) their bank reserve balances at the Fed to earn overnight interest.

But we also note that the Fed actively participates in Treasury repo, both repo lending and repo borrowing:

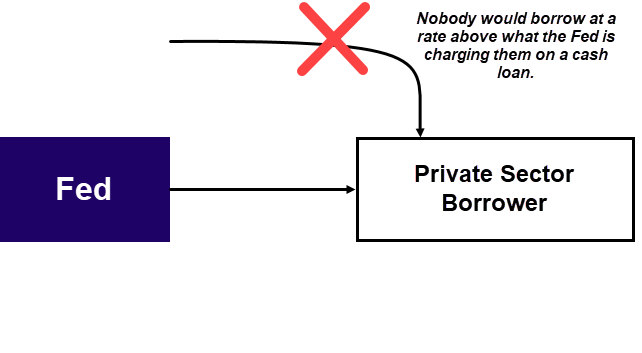

1) Standing Overnight Repos (o/n RPs), or repo lending. The New York Fed lends cash to eligible counterparties secured by high quality collateral.

The Fed’s o/n RP rate sets the ceiling on money rates because a rational person looking to borrow cash would never accept a rate above what the Fed is offering to charge.

The logic underpinning the Fed’s standing o/n RPs (repos).

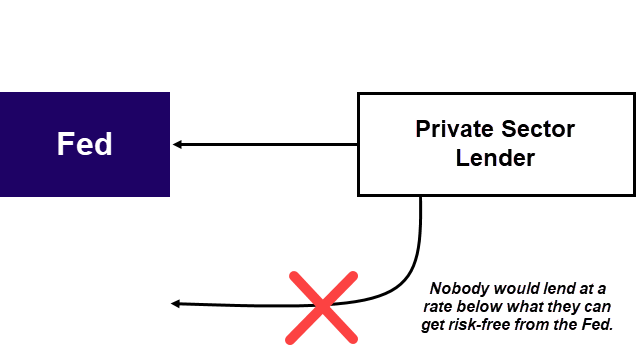

2) Overnight Reverse Repos (o/n RRPs), or repo borrowing. At the New York Fed’s Reverse Repo (RRP) Facility, the Fed borrows cash from eligible counterparties by pledging U.S. Treasury collateral.

The Fed’s o/n RRP rate sets the floor on money rates because a rational person looking to lend cash would never accept a rate below what Fed is offering to pay on that loan.

The logic underpinning the Fed’s o/n RRPs (reverse repos).

Note that, because all lenders in the Fed Funds market have access to lend to the Fed at the o/n RRP, the Fed funds rate will never trade below the o/n RRP rate. The Fed Funds market has been irrelevant for over a decade now.

It’s a repo world.

It’s a repo world: Fed Funds market is just FHLBs loaning to FBOs (foreign bank organizations).

Therefore, the true Fed Funds target range can be thought of as the overnight RRP rate (at the Reverse Repo Facility) at the rates floor and the overnight repo rate (at the Standing Repo Facility) at the rates ceiling. Since 2020, the Fed has not used its overnight repo facility much at all. So, it really remains as only a hard “emergency” backstop on rates – if for some reason there is upward pressure on the rates ceiling, the Fed will provide an infinite amount of dollar repo loans such that the ceiling is never breached.

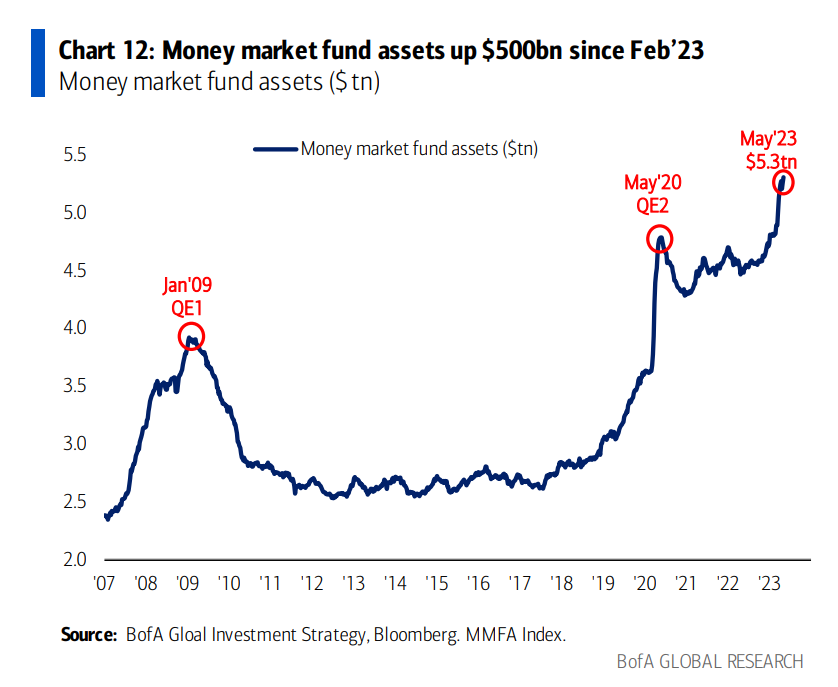

In practice, the vast majority of repo lending is done by money market funds (MMFs), who have $5.5 trillion in assets. That enormous pool of capital is the mechanism through which Fed policy is transmitted in the money markets.

MMFs (or MMMFs) sit on an enormous pool of onshore and offshore dollars, and by manipulating the rates which they seek, the Fed is able to transmit policy via repo.

Any money market instrument must yield more (or equal) than the o/n RRP offering rate, or the MMF will not invest in it (it should also be mentioned that MMFs do not take on credit risk, so will not buy stocks, etc.). For the most part it works well, yet there are also extended periods of time when certain money market rates trade below the o/n RRP floor. This is because there are many USD investors who are not eligible to be o/n RRP counterparties. More on this later (it’s very important).

Therefore, it is clear that the Fed transmits its policy through repo operations.

Porous Ceiling

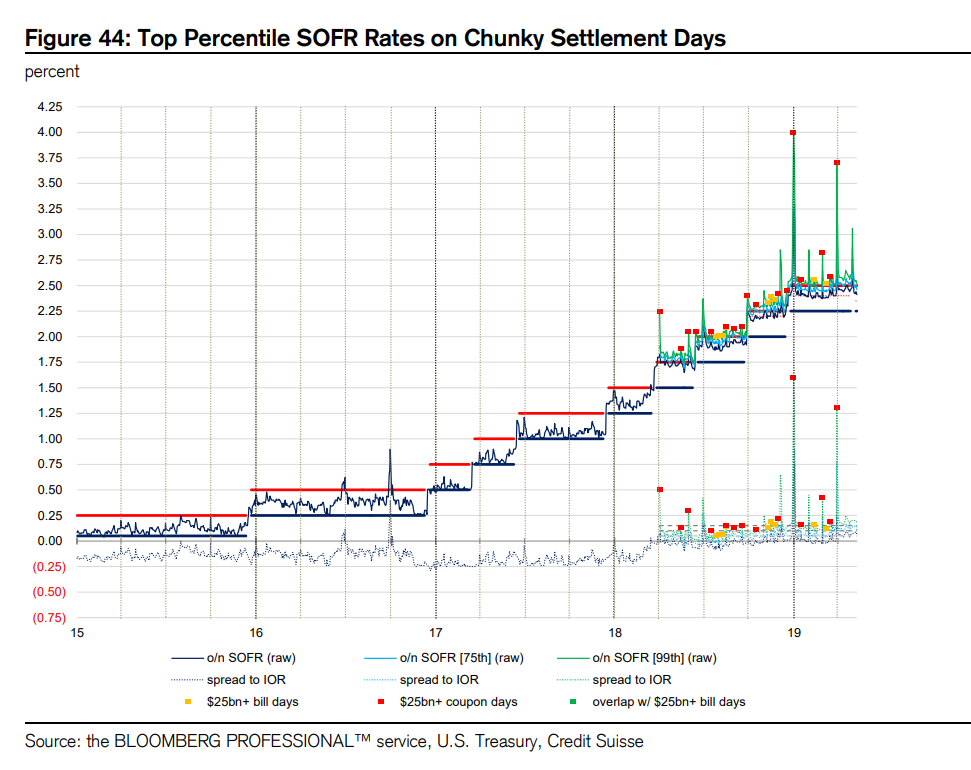

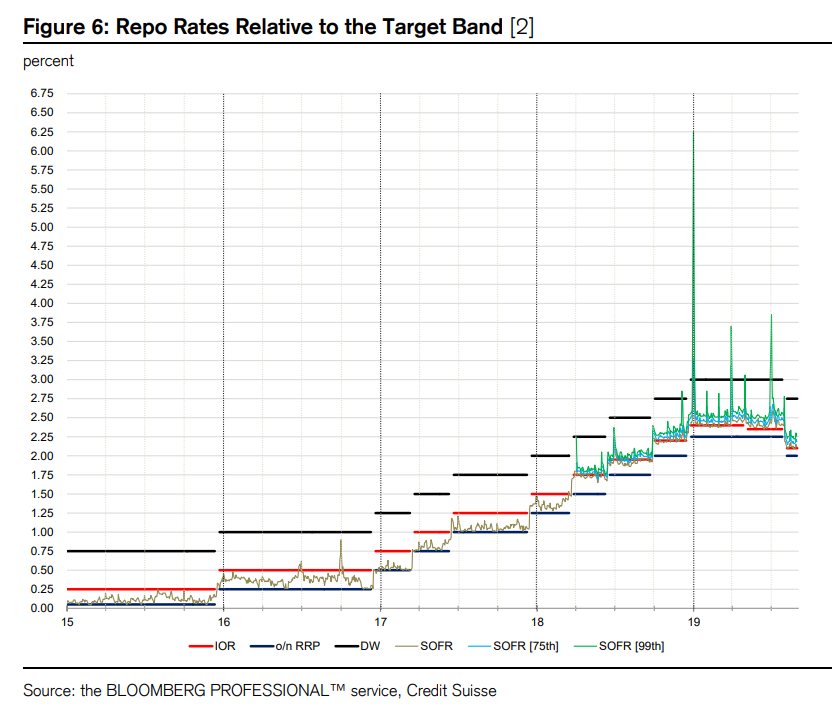

It quickly became clear that the Fed’s post-GFC policy corridor, of transmitting rates through open market operations in repo, was flawed in many ways. Whenever the U.S. Treasury went on an “issuance binge”, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), a proxy for repo rates, briefly collapsed above the target range:

Treasury issuance and inversion of the money market curve increased the frequency of spikes above the Fed’s target range.

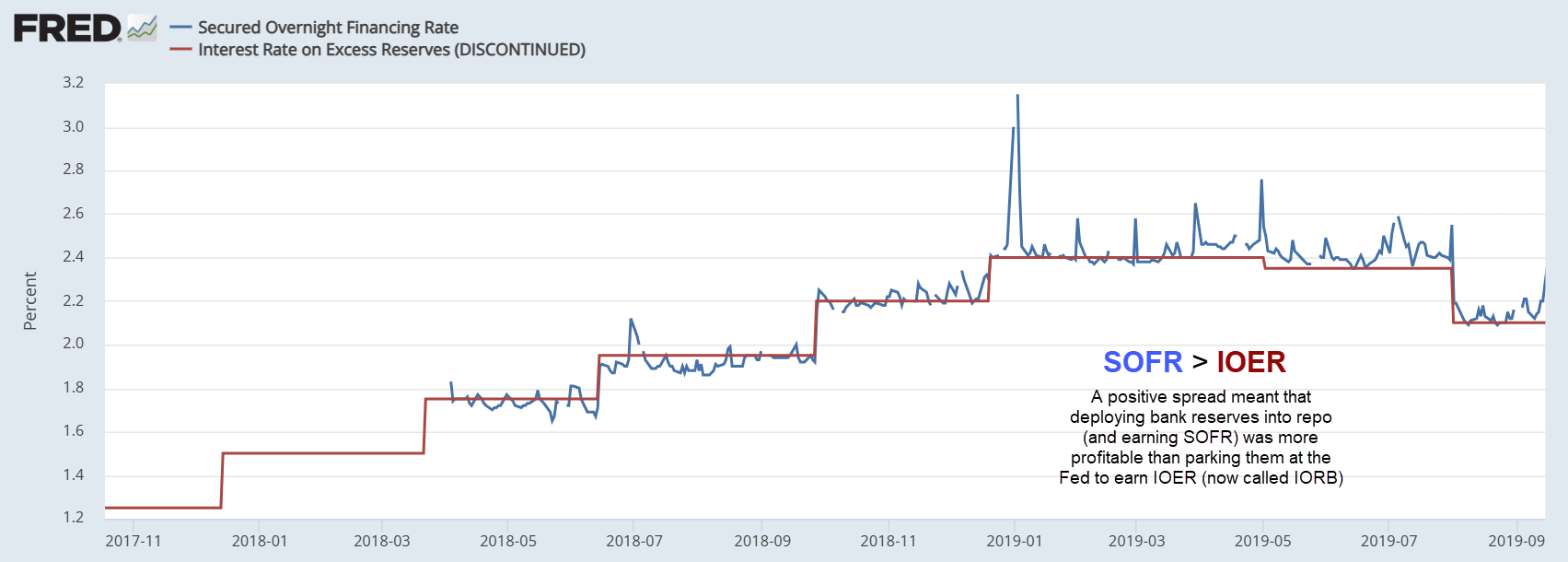

In early 2019, SOFR, the rate earned for lending in repo, began to rise above the interest rate banks earned on their reserves, IOER (now called IORB). It was no longer more profitable for banks to keep reserves parked at the Fed: instead, they would deploy their reserves into the repo market, fast becoming prominent lenders in one of the most systemically important markets (second only to the Treasury market):

Bank reserves are interbank cash and do not leave the Fed’s balance sheet unless the Fed allows the Treasury asset matching them to mature and rolloff.

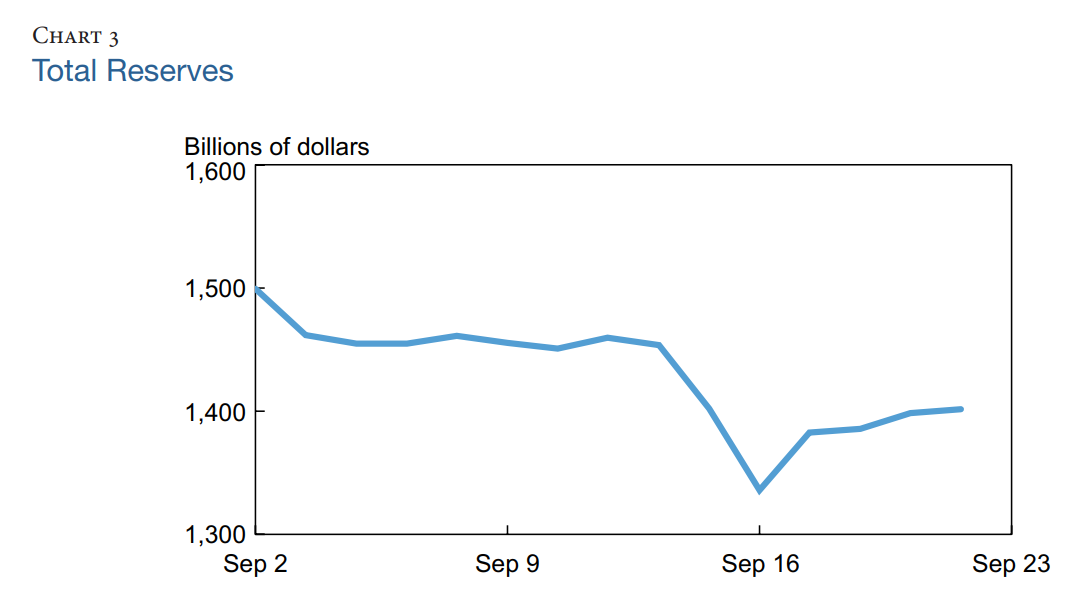

Fast forward to summer 2019 – the decline in bank reserves via Fed “balance sheet normalization” (jargon for QT; reducing the size of the balance sheet and bank reserves in the financial system) had left the banking sector distressed. In July, Deutsche Bank announced it would cut 18,000 jobs. In essence, the banks were “reserve constrained”. Credit Suisse rates strategist Zoltan Pozsar even offered design options for an o/n repo facility such that SOFR would remain contained. It was clear that the ceiling on repo rates was left vulnerable to more frequent and dramatic spikes, and perhaps disaster…

Increasing collateral (Treasury) supply combined with QT (reduced bank cash) was driving repo rates above the Fed’s target range more regularly.

Rates Blowout ‘repo-calypse’

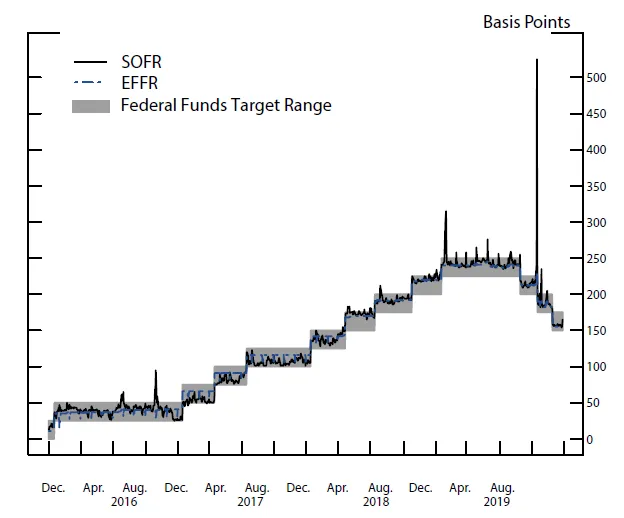

On September 17, 2019, in what became colloquially known as the repo-calypse, both the Fed’s benchmark rate (EFFR) and rates in the repo market shot far above the target range’s upper limit.

Source: New York Fed

A New York Fed paper and OFR report explained it as an unfortunate combination of corporate tax payments from the private sector, taking dollars from reserve-constrained banks who were also mandated to absorb a large issuance of Treasuries on the same day (September 16):

In the week leading up to the rate spike, the Treasury Department issued $78 billion of government debt that was due to settle on September 16, which placed upward pressure on repo rates via two key mechanisms:

First, it reduces the supply of cash available in the financial system because buyers pay for the new debt by withdrawing money from banks and money markets and placing it in the Treasury General Account (TGA) at the Federal Reserve. Second, it generates additional demand for repo to finance purchases of these Treasury securities. A significant share of repo demand comes from primary dealers, who absorb a substantial share of Treasury issuances onto their balance sheets until they can gradually sell them to their customers.

In addition, corporate tax payments for the third quarter of 2019 were due on the same day that Treasury settlement was due: September 16. Corporate tax payments result in a transfer of cash from MMFs, which hold balances on behalf of their corporate clients, to the TGA at the Federal Reserve. As with Treasury settlement, this led to a reduction in the supply of cash available to the repo markets on September 16.

Source: New York Fed “The Market Events of Mid-September 2019”

What could go wrong? A lot – and very quickly – it seemed.

Source: OFR “Anatomy of the Repo Rate Spikes in September 2019”

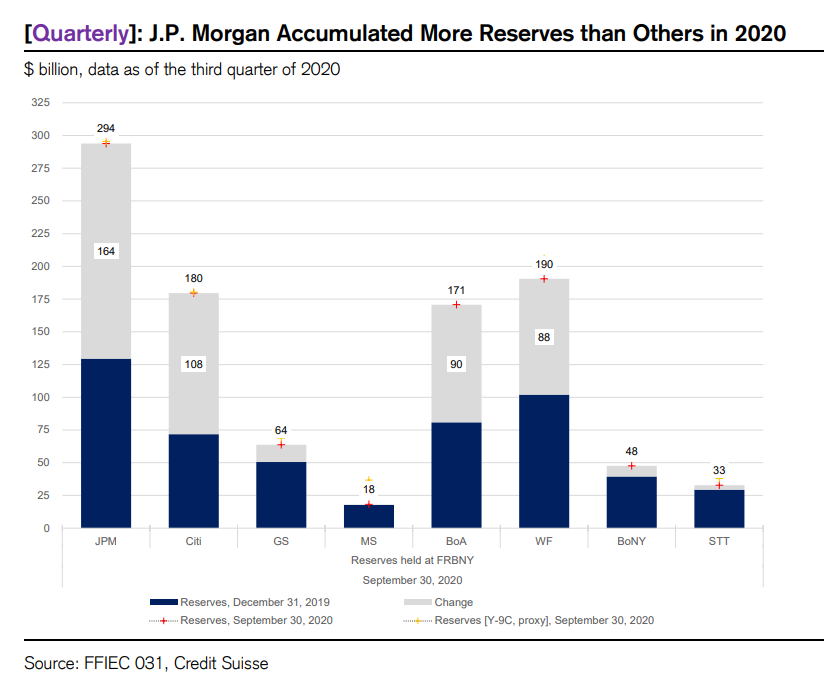

The Fed was then relying on its main foot soldier JPMorgan to bring rates back into place, by deploying its ‘Bakken Shale‘ of reserves into the repo market:

Source: Global Money Dispatch 27 January 2021.

But the Wall Street giant never obliged.

Facing a crisis, while allegedly unsure of a cause, the New York Fed initiated overnight repo operations to push the Fed Funds rate back down to within its target range. The Fed’s liquidity operations were insufficient – banks were still reserve constrained. QE4 of 2020 would solve this, by jamming trillions of reserves into the banking system. All it took was a global pandemic but, after all, …

… it’s a repo world.

The repo-calypse and ensuing QE inspired the creation of the Standing Repo Facility, or SRF. This set a hard upper “jaw” on borrowing costs for all market players, as nobody would borrow at a rate above that offered by the Fed.

But what about the floor?

Leaky Floor

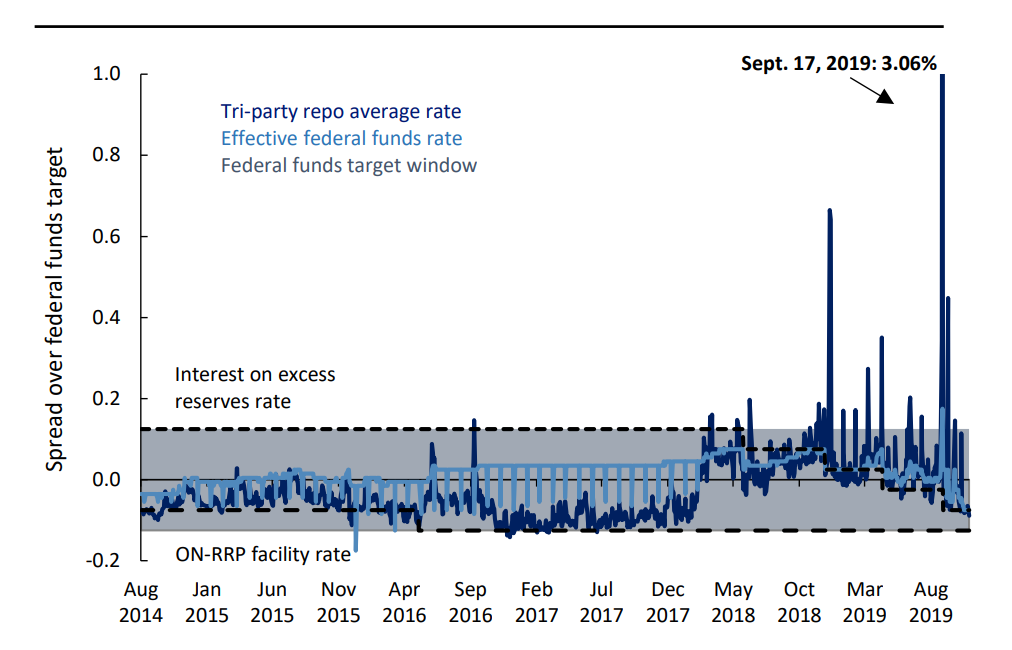

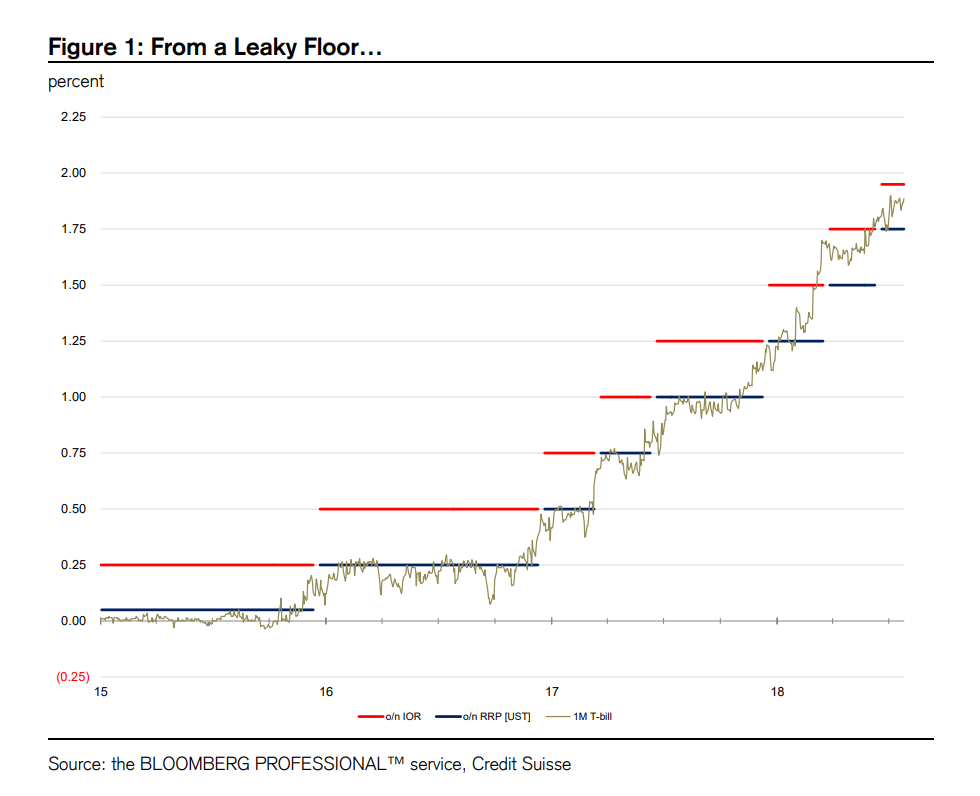

The Fed would like the overnight reverse repo (o/n RRP) facility to play a bigger role in its rate control framework, but for at least a few reasons it has been and will always be a very leaky floor for money market rates. From 2016 to early 2018, Treasury bills consistently traded several basis points below the RRP rate. Figure 1 below shows that other than in the weeks before FOMC rate hikes, one month bill yields typically traded below the administered floor – the o/n RRP rate.

In 2021, the floor only got leakier as money continued to flood into the front end: QE was pouring $120b per month in reserves into the banking system and the TGA drained $800b (recall that a TGA drain is re-balanced on the Fed’s balance sheet with higher bank reserve levels). This abundance of money added to the downward pressure on rates, which were already at the ZLB (zero-lower bound), as news outlets warned:

Recall that the o/n RRP offers certain counterparties (banks, 2a-7 MMFs, GSEs and primary dealers) the option of placing money at the Fed (via tri-party repo) at the o/n RRP offering rate. This gives its counterparties bargaining power such that they never have to invest at rates lower than the offering rate. Therefore, the o/n RRP rate should be a floor on all money market rates.

And for the most part it works well. But not always.

This is because vast pools of dollars don’t have o/n RRP access. Domestically, there are state and local governments (they lend around $200b in repo; check the L.207), private liquidity funds (~$320b in assets; check Table 74), Treasury only 2a-7 investors that cannot invest in repo, as well as pockets of cash held by pensions and corporations.

But more importantly, overseas dollar holders cannot access the o/n RRP and therefore have no firm “floor” on dollar lending rates.

The BIS noted that foreign banks have around $5 trillion in dollar deposits booked outside the U.S. The Fed recognizes the importance of this global system through its FX swap lines, implicitly backstopping the offshore dollar banking system much like the Discount Window backs backstops the domestic banking system.

The abundance of money had indeed pushed repo rates negative in March 2021:

Even the 1st percentile in Tri-Party overnight repo (same market as the o/n RRP) had dipped negative in 2021.

But how is that possible?

Markets and Rates

Broadly speaking, the purpose of markets is to allocate resources that are scarce. Scarce resources move according to price signals to those who are willing to pay the most for them. Resources that are not scarce – like air – have no prices. A decade of QE – culminating in a blowout ‘QE4 finale’ – had made money super abundant to banks, so much so that, technically, it had no value to them. Banks had more deposits than they wanted, and the Treasury has more money than it wanted.

Yet, investors still need a place to park their money. Investors who are only willing to park their money in liquid risk-free assets must buy Treasury bills, and if there are not enough bills (a collateral shortage) their demand will push the yields negative. In a way this is how QE is supposed to work: the Fed, through Treasury purchases, reduces the supply of risk-free assets in the financial system, putting downward pressure on rates since institutions still need to park their money in bills, of which there are now fewer. In doing so, they make cash (in the form of newly-“printed” bank reserves) more available.

The Zero Lower Bound

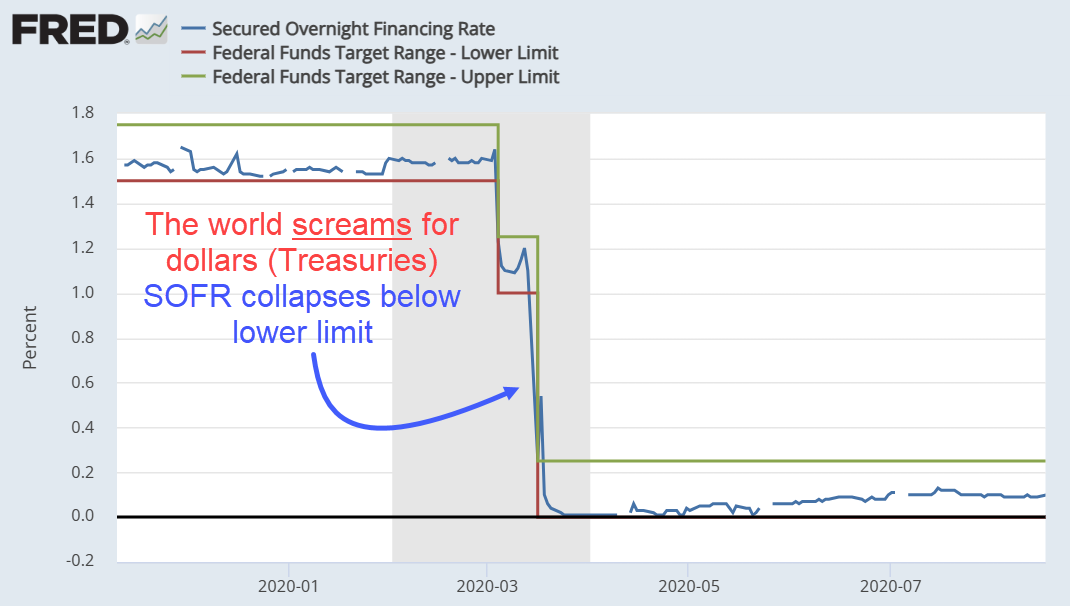

Repo rates trading below zero would have disastrous effects on bank settlement, the dollar standing abroad, and the market for U.S. Treasuries. It’s for these reasons that the Fed is keen on avoiding it. Even the concept of negative interest rates is confusing and awkward.

With negative rates in the repo market, a bank or financial institution would be paying to lend cash – the most basic bank activity. Loans, which were once bank assets, would turn into bank liabilities. What was once a yield-generating asset (like a facility, another name for a loan) would now be a cost-incurring liability.

Negative rates would have damaging implications on the Eurodollar system and dollar standing as well. Say you’re Bangladesh and are rolling over 4-week Treasury bills (just means re-financing once bills mature by using the same money to purchase new bills) that are held in reserve. Instead of earning a small yield on the T-bills, you’re now paying to own the T-bills! Assets have become liabilities, and not only that, but dollar-denominated liabilities (which likely has a much more favorable exchange rate)!

Immediately, dollar obligations would prevent problem-stricken nations from de-dollarizing and piling into, say, euros instead (assuming they are not a negative yield as well). But the damage to dollar hegemony, as even major allies begin to question the extent of their dollar holdings, could be irreparable.

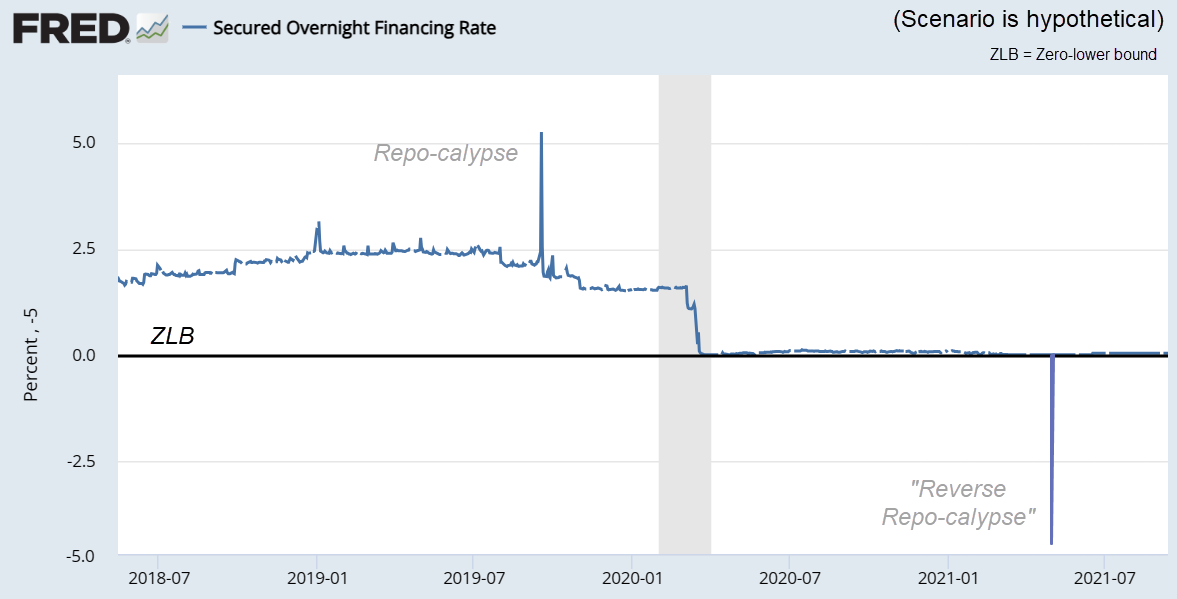

Overnight repo rates did indeed turn negative several times in March 2020 and March 2021, but only by a few basis points (several hundredths of a percent) and for less than a day. The fear was a “reverse repo-calypse“, as the collateral shortage intensified with QE still going on in the background.

The theoretical “reverse repo-calypse”. If repo rates were to print negative, the onshore U.S. banking sector seizes, and FX dollar reserves become liabilities. The Fed would have to act immediately.

It’s fairly simple for the Fed to “fix” a spike in repo rates: just lend as much money as the market demands at some rate. To rectify a spike in the opposite direction, below zero, would be fundamentally different and markedly more challenging. The Fed would have to borrow as much money as the market supplied above zero and open its RRP facility up to more dollars.

Pressure Relief

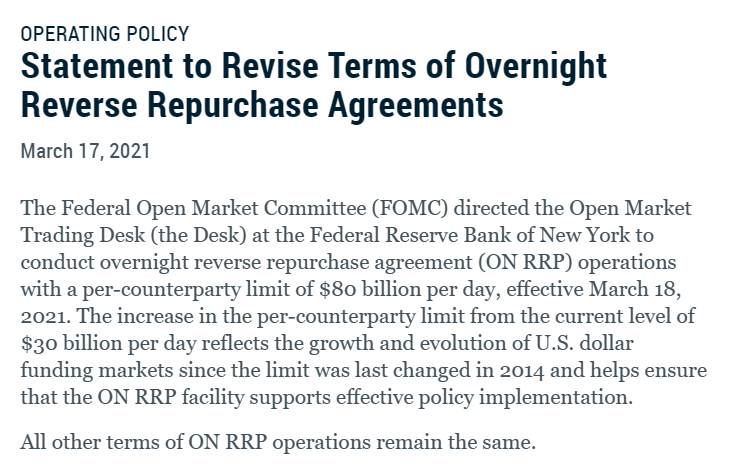

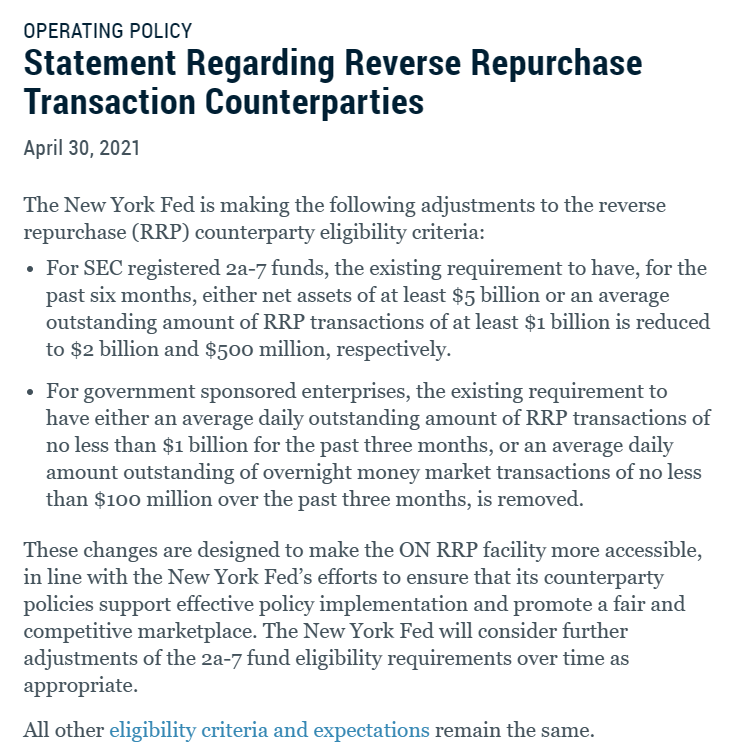

To alleviate pressure on the rates floor, the Fed had to open up its o/n RRP facility to more dollars. It began by increasing CP (counterparty) limits from $30b to $80b:

Then, they adjusted counterparty eligibility to make the facility more accessible:

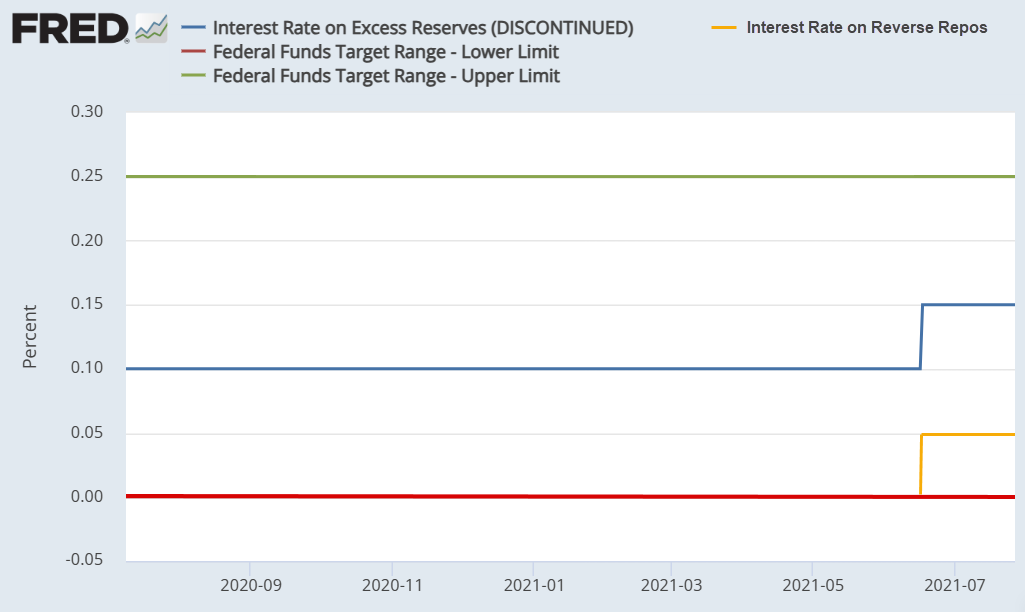

At the June 2021 FOMC (Fed meeting), the Fed decided not to raise their target rate but to raise rates paid on RRP balances (and interest on reserves) from 0 bps to 5 bps:

The RRP rate would from thereon be the lower limit of the Fed’s target range + 5 bps.

From thereon, the o/n RRP rate would be lower limit of Fed’s target range + 5 bps.

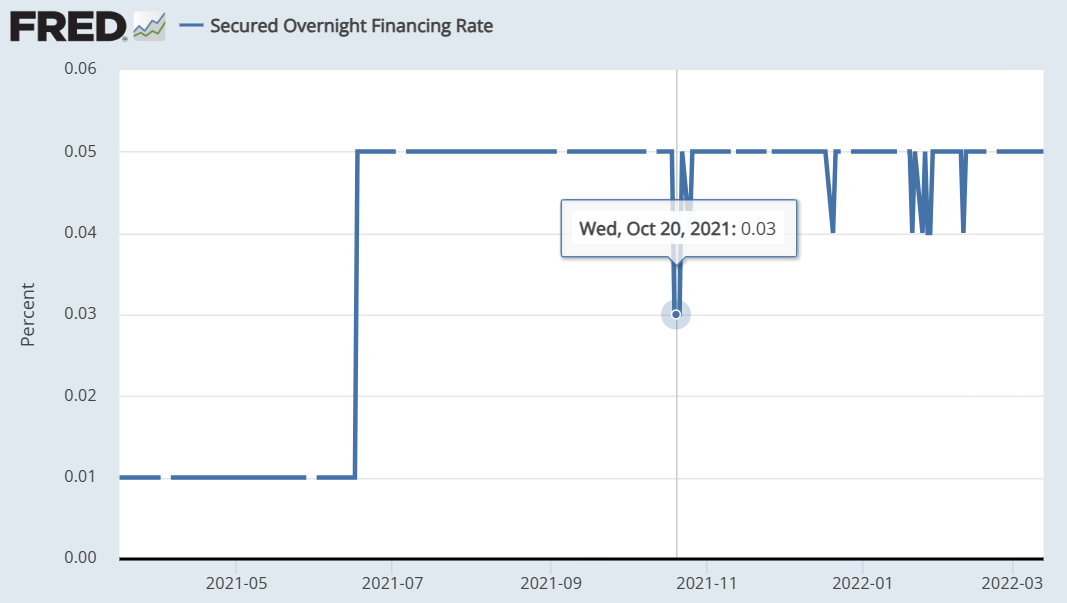

This seemed to work for the summer, but even after all of these adjustments (including tweaking counterparty limits again from $80b to $160b in September), within a few months the Fed still could not secure the money market rates floor:

SOFR dipped to just 3 bps – below the 5 bp floor set by the RRP rate – on October 20 2021.

Come Hell or High Water

Raising repo rates higher still, by toggling the entire target range, was the only option the monetary alchemists at the Fed had left (short of redesigning the o/n RRP facility). It would require a dramatic rate hiking cycle and, knowing that things would inevitably “break” as rates plugged along higher and higher, a diligent focus to keep them high in the face of the damage and political pressure.

At the time of this article, the FFR (Fed Funds rate; the interest rate) was at 3%. Powell had no choice but to go higher.

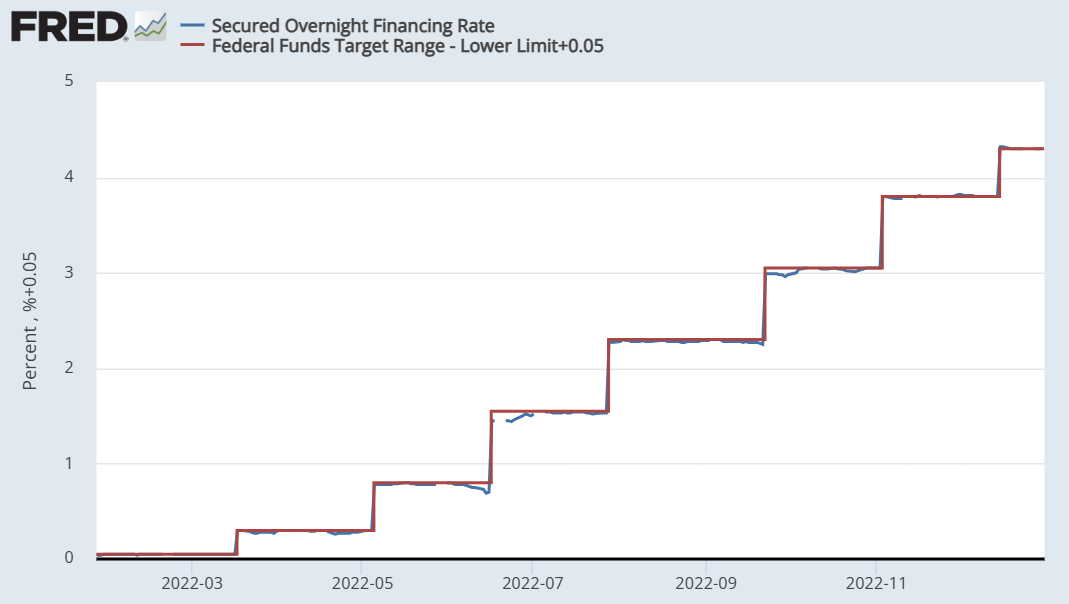

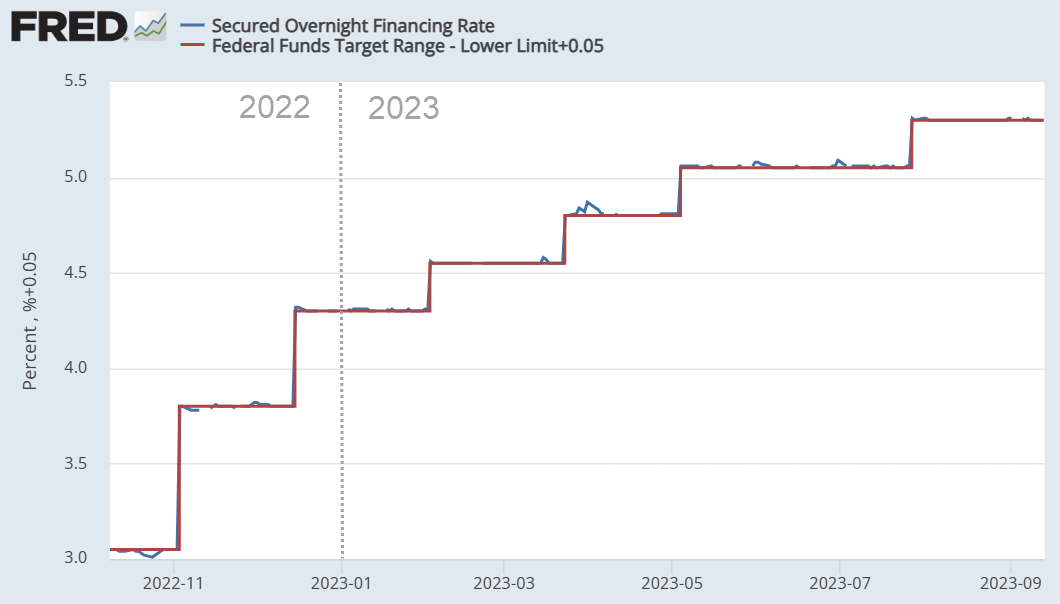

Even during the first few hikes of 2022, SOFR quite consistently traded below the o/n RRP floor rate:

Throughout 2022 with rates under 4%, the RRP rate (red line) was still a very leaky floor for repo rates (proxied by SOFR; blue)

It wasn’t until this year, with repo rates firmly above 4%, when SOFR no longer dipped below the o/n RRP rate (ironically, 4% is the same target the Fed had said they’d hike to at a minimum “come hell or high water“. That is not a coincidence, and it should be obvious why):

SOFR (blue) has not yet printed below the o/n RRP rate (red) in 2023. This can probably explain why the uptake at o/n RRP facility peaked in December 2022, and SOFR volumes have increased this year by a significant margin.

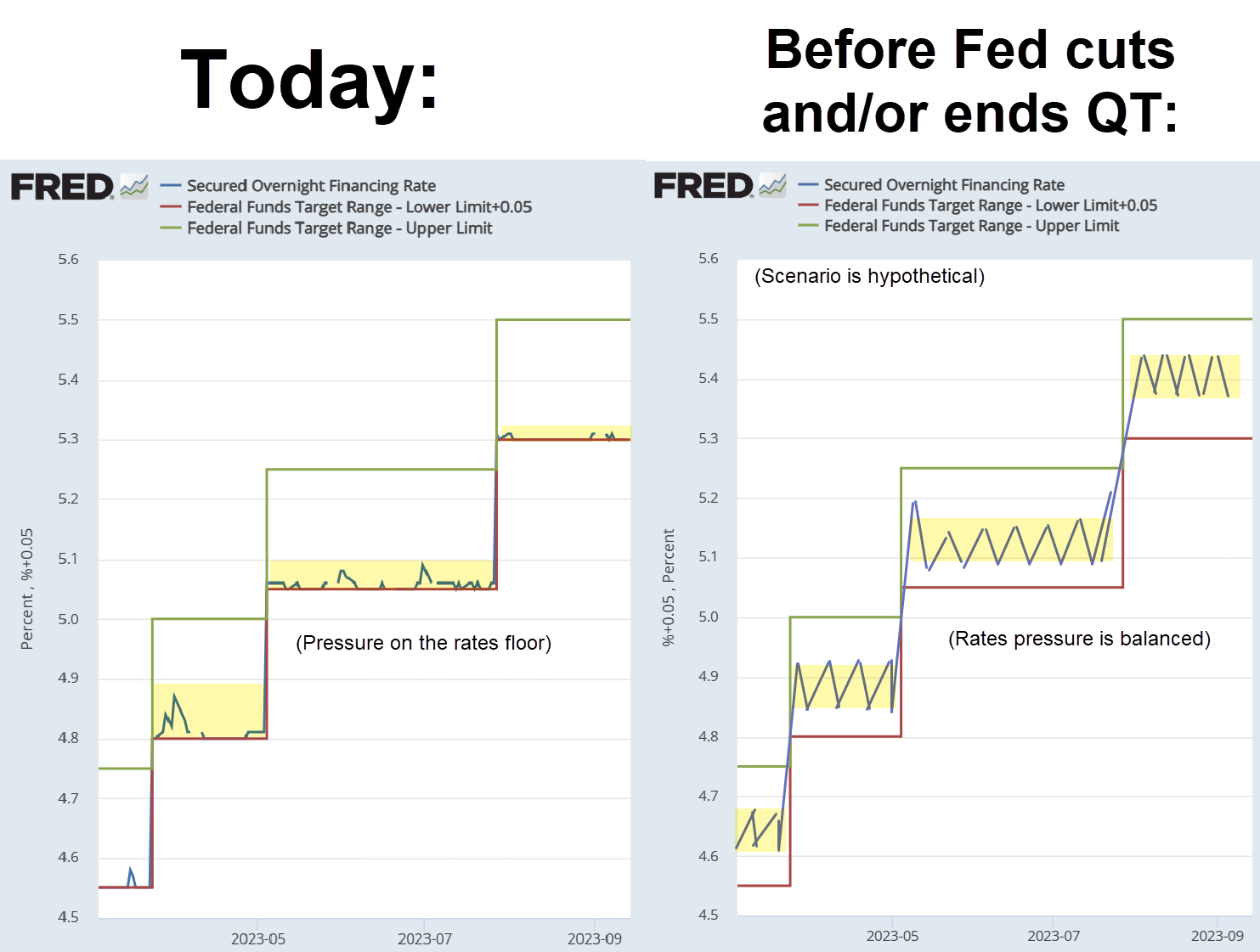

Ideally, the Fed would like for repo rates (SOFR) to trade comfortably above the RRP rate, but also comfortably below the repo rates ceiling. Doing so may require additional hikes and QT (which drains money from the financial system, thereby taking pressure off the floor):

LEFT is how repo rates (proxied by SOFR) are trading as of September 14; RIGHT is how the Fed would like SOFR to trade before it can officially pivot or end QT. Essentially, pressure has to be taken off of the rates floor, and this is both a function of rate hikes and QT.

Additional hikes beyond 6% could only be sold to the public in the presence of rebound inflation, at least I would assume. Core PCE would need to return to 5% (June 2022 levels) for the Fed to sensibly tell the American people that they are prepared to keep going higher. And with interest rates as high as they are now, only Washington D.C.’s deficit spending could reignite inflation that dramatically.

~

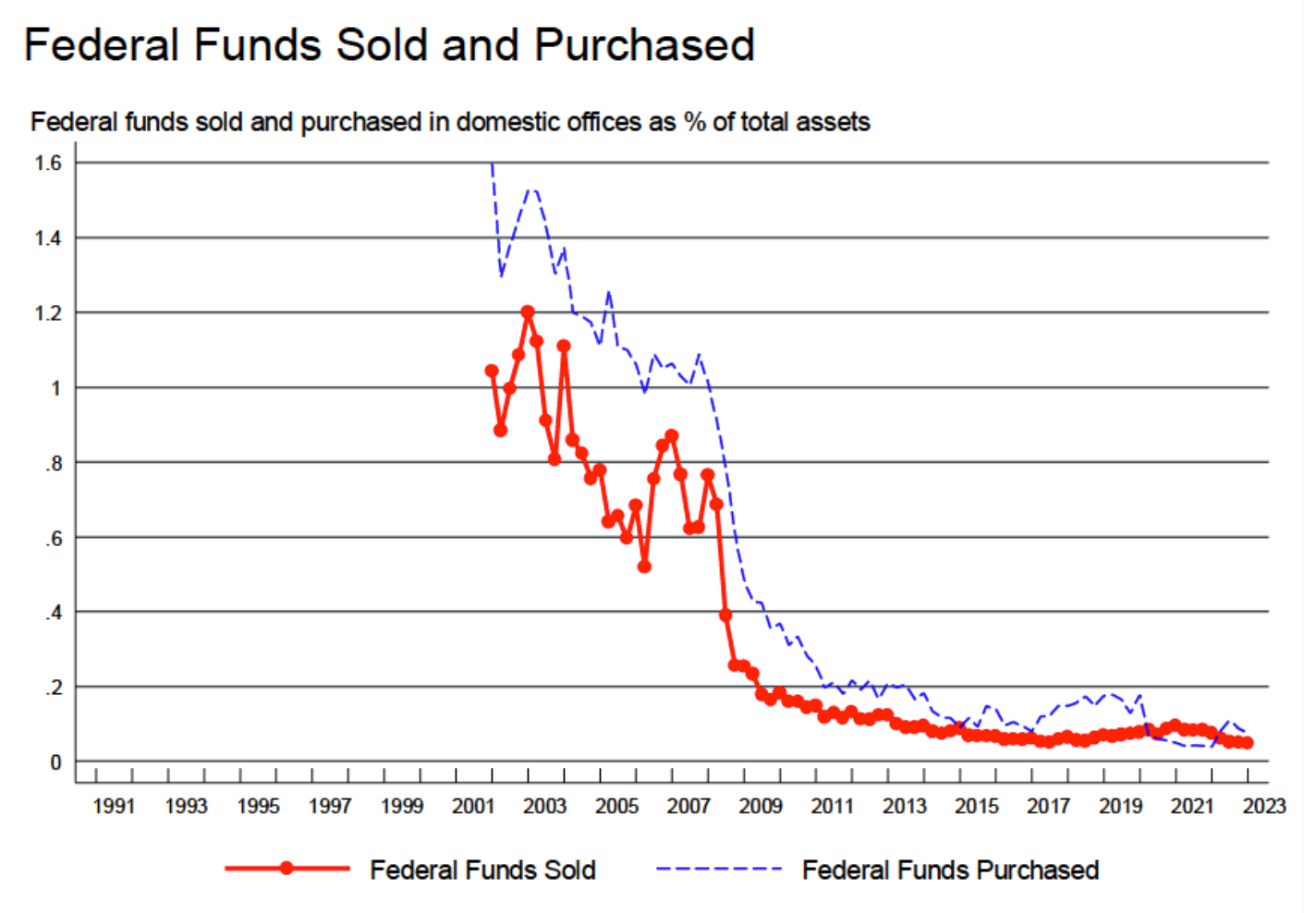

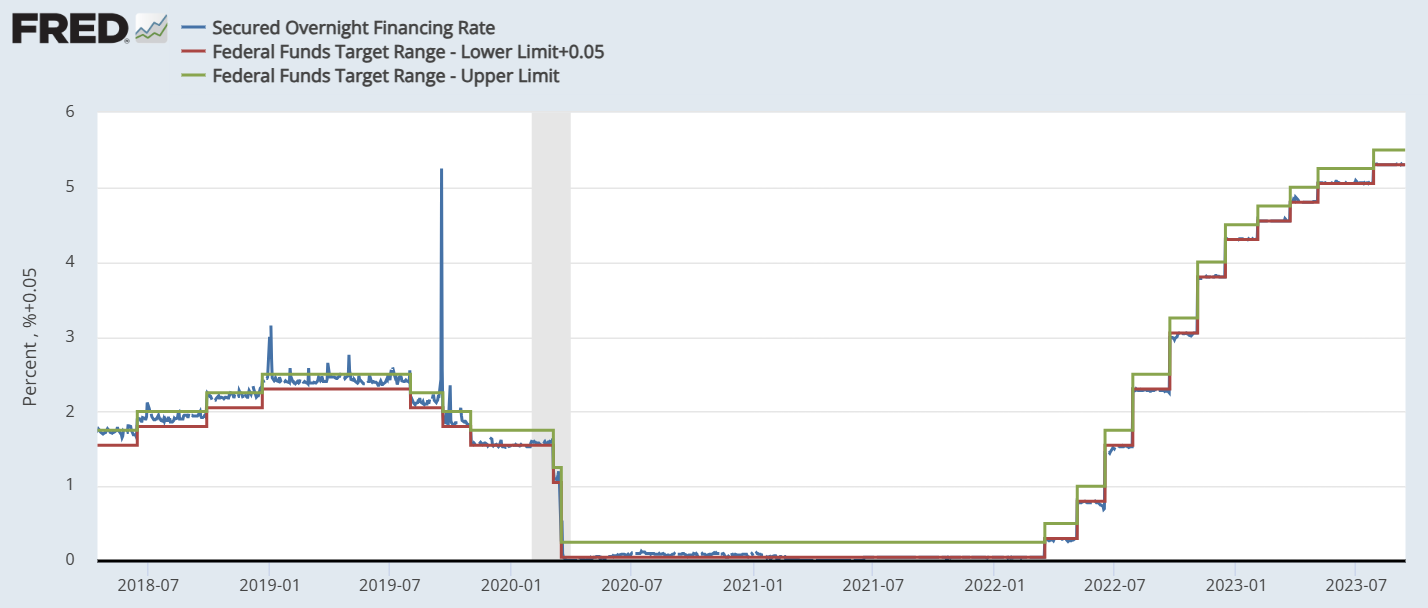

Revisiting (a slight variation of) the first chart we posted; here we can observe two qualitative facts:

1) Before September 17, 2019, the day rates blew out of the top of the Fed’s upper limit, the net repo rate pressure was clearly on the “upper jaw” – the top ceiling.

2) Since September 17, 2019, the day the New York Fed began trillions in overnight repo (and reverse repo) operations, the net repo rate pressure is clearly on the “lower jaw” – the bottom floor.

The introduction of the Standing Repo Facility was in a sense the creation of a hard upper jaw on dollar rates. By “hard jaw” we mean a non-contestable limit, a barrier that will never be breached. It’s only logical that the Fed will briefly lose control of the rates floor one day and, in response, create a new facility to patch it up. Or perhaps re-vamp the existing RRP to make it globally accessible.

As my friend Concoda says regarding “The Fed’s Global Dilemma“, since every other defect in the Fed’s jaws has been pushed to the point where officials had to intervene, a global “hard lower jaw” seems inevitable:

At some stage, most likely when the Fed’s tightening prompts a more significant credit crunch, monetary leaders will choose to patch the hole in its global jaws, once and for all. The Fed will open up access and offer liquidity to anyone, especially those posing risks to the status quo. Foreign entities will gain entry to the facilities that offer dollars within Fed-approved rates, and only then will the Fed’s jaws be complete.

What provokes the U.S. central bank to make such a move, is now the more pertinent question.

We can guess that it will be in the form of collateral (Treasury) shortage, which means a dollar shortage. In other words, it will be a COVID-like dollar funding event that puts intense downward pressure on the rates floor. March 15-16, 2020, an early peak of COVID lockdowns, was indeed the last time SOFR collapsed 50 bps below the Fed’s lower limit, forcing them to respond only hours later with an emergency rate drop:

Had the Fed sat on their hands on March 16, 2020, repo rates would’ve probably tanked negative.

There’s really no version of a timeline for the rates floor to be breached, and thus a new Fed facility to be born. It’s important to pay attention to where repo rates (SOFR, TGCR & BGCR) are trading relative to one another and relative to o/n RRP. Just as SOFR quietly drifting above IOER in early 2019 would set the stage for the repo rates ceiling to fail (and COVID-19), so too could a quiet shuffle in repo rates set the stage for the floor to fail.

Generally speaking, I am paying attention to the spread between repo rates and o/n RRP. Repo rates are proxied by SOFR but also TGCR and BGCR. When/if SOFR crosses back below the o/n RRP rate, RRP usage will increase, since it will be more profitable for MMFs to lend their cash to the Fed versus lend it in repo. If this spread begins to grow (absent debt-ceiling drama) it could indicate the early stages of another collateral shortage (this example from Jeff Snider is why I stress ‘absent debt-ceiling drama’).

~

If this hypothesis is true, what does all this tell us?

1) SOFR is king: The Fed is paying closer attention to where SOFR trades relative to the FFR (Fed Funds target range) than where core PCE (the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge) trades relative to 2%.

2) No pivot: Interest rates will not return to zero and inflation will be persistent, at least until the Fed designs a new facility to act as a global floor on dollar repo rates.

~

This was originally posted to the DissidentThoughts Telegram and written by 𝕲𝖊𝖗𝖍𝖆𝖗𝖉 𝕾𝖈𝖍𝖗𝖆𝖉𝖊𝖗. This is not investment advice nor necessarily even true, but the compilation of many hours of research.